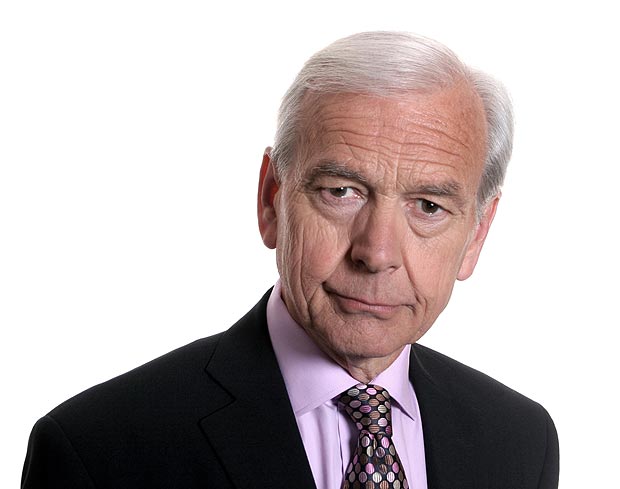

THE GREAT FOOD GAMBLE—By John Humphrys

Preface

I started thinking about this book in the early nineties when the full horror of BSE was becoming apparent. Many people were beginning to ask serious questions about the food on our table and to worry about food in a way we had not done for generations. I thought then that we needed a proper national debate that would address the most fundamental questions: the sustainability of our farming system, its effects on the environment and, most of all, the safety of our food. Sadly, it took another great farming crisis to bring about the debate of this book, first published when the crisis was at its peak.

It was, of course, the foot-and-mouth epidemic. The question on which it has focused it’s attention—and one that should have been addressed many years ago—goes to the heart of Britain’s food policy since the Second World War. Has the relentless drive for more and more cheap food proved a mistake?

The most powerful voices in the food industry have always scoffed at even a hint of doubt. They have told us it is naive even to raise the question. They remind us that choice is more varied and shopping for food has never been more convenient. Above all, they say, food is cheaper than it has ever been. The only alternative to the way we have been farming, producing and distributing our food for half a century is to return to some primitive form of agriculture and food production that would lead to desperate shortages, sky-high prices and disease-ridden animals. We would be back in the Middle Ages. Some talk darkly of malnourished children, even the return of diseases such as rickets.

Most of that is hysterical, self-serving nonsense and it is increasingly being seen as such. Malnutrition is a function of poverty or ignorance or both, not of the availability of food. I have spoken to doctors who worry about some of their young patients because they are fed a diet of junk food. Their parents have never cooked them a meal of fresh meat and vegetables in their short lives. And the reasons for this are nothing to do with the price of food. On the contrary, processed food is invariably more expensive than fresh vegetables. It is, to use the jargon of the day, a ‘lifestyle’ choice and one that is encouraged by the industry. Quite simply, there is more profit in a bag of crisps than in a pound of potatoes.

Nor is a return to ‘primitive’ farming practices the only alternative to factory farming and highly intensive agriculture. To say so is gross insult to farmers who care deeply for the welfare of their animals and do not regard them as mere units of production. It also ignores the advances made in less intensive farming technologies. A growing number of farmers are finding ways of achieving good yields without tearing open yet another drum of chemicals or bag of synthetic fertiliser.

The big question the industry and most politicians have been so reluctant to address is whether ‘cheap’ food is really cheap. To do so is to raise doubts about their judgement or even their motives. What price, for instance, should society put on the destruction of so much of our rural heritage, the loss of our water meadows, ancient hedges and wild flowers, the disappearance of so many songbirds?

It may be impossible to calculate that sort of thing in hard cash, but much else can be quantified. There are the taxes we pay to finance farming subsidies, many of which go to some of the wealthiest farmers in the land to grow food we do not need—or even to pay them not to grow it. There is the cost of cleaning chemical pollution from our drinking water. There are the consequences for the National Health Service of factory farmers abusing antibiotics. There is the possible impact on our health of chemical residues in our food. There are the long-term effects of soil erosion and declining soil fertility. There is the terrible impact and vast cost of a tragedy such as BSE. And, most recently, there has been the disaster of foot-and-mouth disease. It may not have been the direct result of intensive agriculture, but good husbandry is the first thing to suffer when farmers feel compelled to stock many more animals than they can properly manage, and modern practices in food production and supply have enabled it to spread at a terrifying speed across the entire country.

Is it naive to raise questions about a food policy that has created such a legacy? I think not. That is the reason I have written this book. Some of the things I have learned while researching it have worried me a great deal. But this is not a counsel of despair. A growing number of farmers and food producers accept that mistakes have been made and are searching for better ways of doing things.

As for politicians, it seems they may finally have got the message. All parties now claim to see the error of past policies. Tony Blair himself has said he shares many of the concerns expressed in this book. But whether the politicians’ actions will fit their words remains to be seen. The old Ministry of Agriculture (MAFF) was formally killed off soon after this book was first published—at least in name. We have yet to see if its successor will put right so many of the things MAFF got wrong.

What is clear is that we, the consumers, are no longer prepared to take our food for granted. We recognise the difference between good, affordable food and cheap food produced with little or no regard to quality and sometimes scant regard to safety. We know there is a better way of doing it.

John Humphrys focuses on seven main areas, the history of our food, pesticides, the soil itself, fish farming, antibiotics, GM and the move toward organics. His passion and convincing supportive evidence in this compelling read are portrayed in the intriguing perspectives that he reveals. He describes a farm that would be found anywhere in England in 1950, and then effectively shows in a short time period of just 35 years up to 1985, what a dangerous shift in farming practices and attitudes had taken place. He then takes his hypothetical vision into the future into 2020. And what he sees is alarming. In fact, in the five years since the book was first published, some of what he describes has already become an all too familiar and frightening reality. Although sounding an alarm, the book is positive in its message particularly when it focuses on organics in its conclusion. This inspiring examination of how our food has changed and deteriorated since 1950 will be sure to help you realise how important it is that we look after ourselves and our families.